Most popular in the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, Japanned work was created as a way to "knock off" heavily lacquered and decorated pieces being imported from the East -- primarily China, Japan, and India.

nineteenth centuries, Japanned work was created as a way to "knock off" heavily lacquered and decorated pieces being imported from the East -- primarily China, Japan, and India.

For an informative article on the history of Japan work written by Louise Devenish, click here.

photo courtesy 1stdibs website

This secretary is an example of a piece you will see in her article.A term you will often see associated with

Japanned goods is chinoiserie. "Chinoiserie" comes from the French, and refers to European or Western items that have been decorated with fanciful interpretations of Chinese scenes.

Japanned goods is chinoiserie. "Chinoiserie" comes from the French, and refers to European or Western items that have been decorated with fanciful interpretations of Chinese scenes.

Examples of chinoiserie can be found in painted wall coverings, textiles, applied and structural decorations, and painted accessories and furniture.

photo courtesy Made in the Black Country website

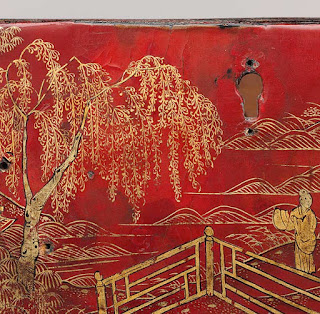

This tilt top table, depicting a stylized "Chinese" scene is an excellent example of Japanned chinoiserie.The red Japanned and gilded chinoiserie table shown here is a stunning piece.

You can learn more about this piece, made for Louis IV, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

The detail on this drawer front is just incredible.

Although different interpretations of Japanning techniques were developed in other countries, parts of England became especially well known for their Japanned products.

photo courtesy Wolverton Art and Museums website

Of course, not all Japanned articles are furniture, nor was it made only for kings. The crumb tray and brush shown here, is an example of a utilitarian piece that would have been produced for the rising middle class. Even in the photograph, the visual depth achieved by layering the decorative elements and lacquers is evident.This paper mache box is another example of a small utilitarian piece.

Photo courtesy Gasoline Alley Antiques

The decoration depicts a Father Christmas, with Eastern inspired designs on the borders of the box.The tin tray shown here is an example of Japanning on tin ware, often referred to as tole (not all tole is Japanned, however).

photo courtesy Wolverton Art and Museums website

In this case, the decoration is achieved through one-stroke folk painting techniques rather than by depicting a chinoiserie motif. The border is painted in a simple, Gothic inspired quatrefoil design.This teapot stand is another example of a utilitarian piece produced for the middle class.

photo courtesy Made in the Black Country website

An interesting article about the social implications of items as simple as this trivet can be found here, on the Made in the Black Country website.My favorite piece, however, is this unapologetically non-utilitarian wall plaque.

photo courtesy Wolverton Art and Museums website

First of all, it is not in the least bit pretentious. It feels like a nice "homey" bit of folk art. This is definitely "art for the masses" (perhaps we'll see some knock-offs of this piece in a Pottery Barn catalog someday). The faux bois detailing is absolutely charming. This piece represented "art for art's sake", but pieces like it were accessible to anyone.Art for art's sake has been important in all levels of society -- whether it be in a king's palace, in the parlor of a member of the rising middle class, or in the living room of a peasant worker. I think that is why I am drawn to Japanned items -- not only did the inspiration for the technique span continents, but access to Japanned items spanned socioeconomic levels.

This post is being linked to Alphabe-Thursday, at Jenny Matlock's blog, and to Colorado Lady's Vintage Thingie Thursday.